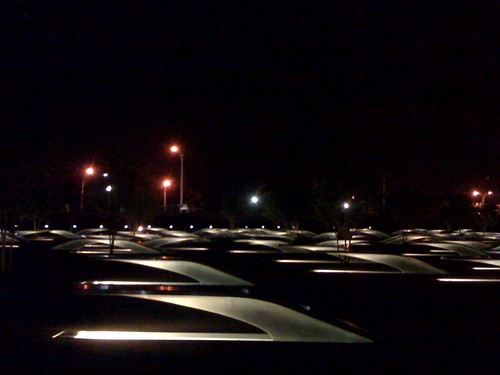

A couple weeks before I left America last year, on a tepid, early summer night, I visited the Pentagon memorial for the first time. There are 184 benches laid out in opposite directions, each hovering over a small pool of water. The benches that face the Pentagon are for the people who were in the building, so that when you read their names, you see the Pentagon in the background. The benches facing the other way remember those who were in the plane. They face the sky.

The benches are arranged in rows representing years of birth. The first row represents 1998. It has one bench; Dana Falkenberg was three. When you look at Dana’s bench, you see the sky, and inscribed inside the little pool below, you see the names of her family members, the ones we also lost. Her parents were taking her and her older sister Zoe to Australia that day. Their mother, a Georgetown professor, was going to be a visiting fellow. To get to Australia from Washington, you have to fly from Dulles to LAX first. And you have to do this on American, so that you can connect in Los Angeles to the Qantas flight that will take you to Sydney or Melbourne or Canberra, which is where Dana was going. The Falkenbergs were flying from Dulles to LAX on American Airlines flight 77. Thirteen days after visiting the memorial, and nine years after I first arrived in America, I flew from Dulles to LAX on American Airlines flight 75, before catching the Qantas connection to Sydney. I was going home.

On the twenty-fifth anniversary, my kids will watch me watching the reading of the names, and they will see me come close to tears whenever a family member comes to the end of her list of about a dozen names and, still struggling to say the words, ends with, “And my father, we miss you and we love you.” My kids, or maybe on the fiftieth anniversary, my grandkids, will see my eyes well up and they will ask, were you there? Did you know anyone? Did you know anyone who knew anyone? And to all these I will answer no. So why are you crying then?

I’ve never really been sure. In the days and weeks after September 11, in the common room of my freshman suite, I could not pull myself away from the TV and the stories of survivors and the bereaved, and those still searching. There was something compelling about the heartbreak, maybe something vulnerable about this country I had thought I knew and yet just started to know, the same way you don’t want to pull away from a conversation with someone who has just or finally opened up to you, who has just or finally revealed what it is that makes them hurt; their hopes and, yes, their fears. Maybe in the ten years since, as I’ve come closer to learning about grief and loss, and maybe in the years ahead, as I am sure to learn more, maybe the names and the stories affect me more, reach deeper into my soul and squeeze tighter. There is so much to say, big ideas about war and peace, about government and religion, about human rights and civil liberties, about how we interact, how we respond to crises and how we, as people and as nations, deal with loss. How we grieve. There is so much to say, and yet I don’t know what, or how. I think if they ask, if my kids or grandkids must know why something so long ago can still make me cry, I will tell them about Dana Falkenberg. I know I will still remember her name.